Robert E. Alker Art

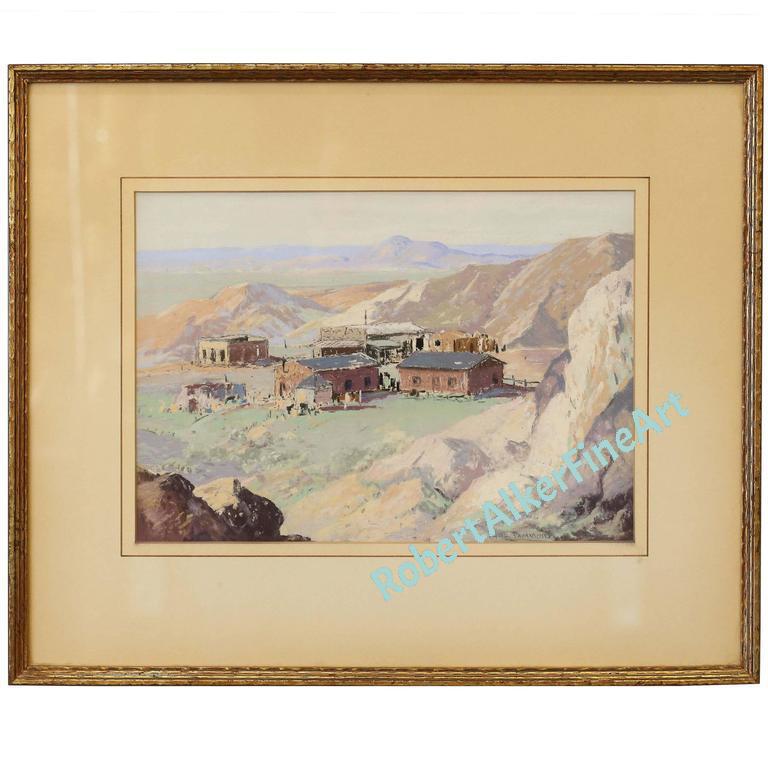

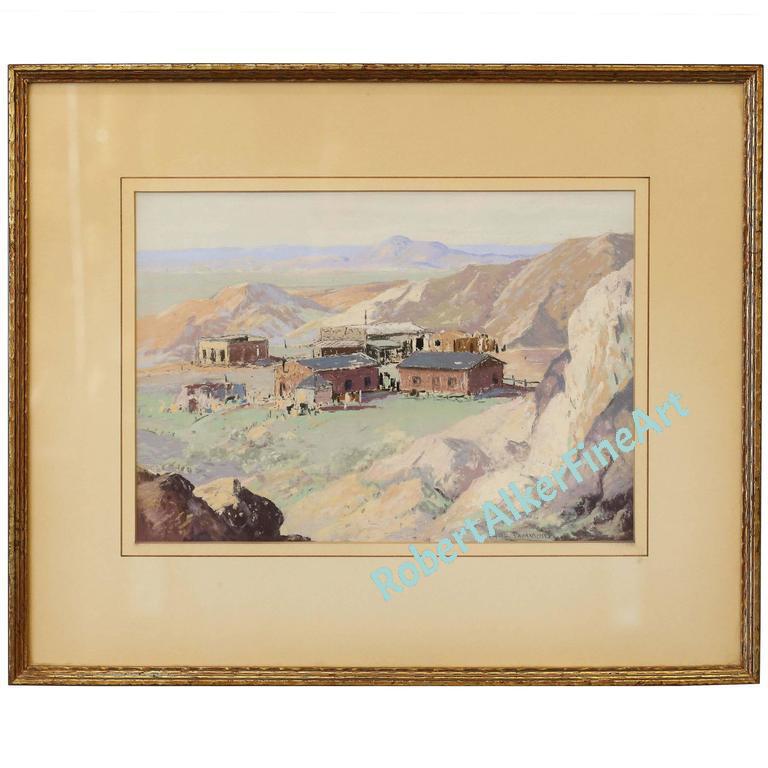

Carl Sammons (1883 -1968)

Carl Sammons (1883 -1968)

Couldn't load pickup availability

American Artist.

Pastel on cardboard. Signed lower right. c. 1930s

9.5"h x 13.5"w, overall size is 16.5" x 20.

Carl Sammons was one of the noted early California Impressionists. He was a long-time resident of the San Francisco Bay Area and a prolific Plein Air artist. Sammons is known best for his California representational landscapes and coastal scenes. While much of his work was done in California, he traveled and painted throughout the West. In his early career, Sammons painted Tonalist pastels and some sources list him as a Pastelist. However, around 1920 Sammons added vivid color and Impressionistic brush strokes to his repertoire. At the same time he began painting oils and these comprise the majority of his work. The renowned early California Impressionist John M. Gamble praised Sammons’ work on several occasions and was reported to have said that Sammons was the best painter of flowers in the west. More recently, Alfred C. Harrison, Jr. of The North Point Gallery, San Francisco said that Sammons was the best pastel landscape painter America has produced.

Carl Sammons was born in Kearney, Nebraska to John B. Sammons and Elizabeth (a.k.a. Lizzie) Danford Sammons on May 9, 1883. Many sources list Sammons’ birth date as May 9, 1886. However, at the time of the 1885 Nebraska State Census, two year old Carl and his family were living in the Riverdale Township, Buffalo County, Nebraska. The 1900, 1910 and 1920 United States Federal Census further confirm Sammons’ birth date as 1883. He was the seventh of eight children. Sammons’ mother and father were both born in Ohio. His father was a farmer but served in the Union Army during the Civil War.

Sammons grew up in Kearney, Nebraska and began working as a sign painter there. In 1905 Sammons moved to Sioux City, Iowa and began working for Ashley & Loft, a sign painting company where he painted signage up to and including billboards. Although he worked in Sioux City, he kept his legal residence in Kearney (as evidenced by his name being listed in the 1910 Kearney Federal Census and the 1910-1911 Kearney City Directory). Sammons went on to work for the Sioux City sign painting companies Arthur Loft in 1909 and 1910 and C W Ashley in 1911 and 1913.

Later in 1913, Sammons moved to Petaluma, California where his sister, Mary E. Dye, lived. By the spring of 1916, Sammons had moved to Monte Rio, California where he opened an art studio. Sammons lived in Oakland, California in 1917 and moved back to Kearney later that same year. Based on the Federal Census, Sammons’ father passed away between 1910 and 1920. It’s possible that his father’s passing was the reason Sammons returned to Nebraska when he did. In early 1920 Sammons joined the local chapter of the Elk’s Lodge in Kearney.

Even though he had put down roots in Kearney, Sammons hadn’t forgotten California and he returned to the state in 1920 when his mother moved to Long Beach, California. From then on, Sammons earned his living solely as an artist and called California his home. At least five of his siblings (the five youngest) eventually moved to California.

On February 3, 1923, Sammons married Queen Esther Stewart. Queen, a native Californian, was born on May 14, 1893 to Calvin Stewart and Frances Julia Cooper Stewart residents of Fort Bragg. Queen was the youngest of seven children. At the time of their marriage, Queen was living in Petrolia (one of Sammons’ favorite locations to paint). Sammons and Queen had much in common: a love and appreciation of California; a religious belief in God; and both came from large families whose parents were born in the Midwest. This was the first and only marriage for both of them. They were married in the Oakland home of a friend, F. E. Lucas, by the minister of the First Lutheran Church, Oakland. They settled in Oakland and traveled widely throughout the West. During their first years of marriage Queen went by Bess or Bessie.

Sammons was a quiet, soft spoken and gentle man who was heavily influenced by his Midwest upbringing. Nevertheless, in some ways he was a contradiction. He was a very private man; yet he was also a warm and friendly person who waved to passers-by while outdoors painting and sketching. He eschewed the limelight but enjoyed the children who would occasionally watch him paint, sometimes sending them on errands to fetch something for him, e.g., a piece of redwood bark so he could get the color right in his paintings.

Sammons was a careful and deliberate person. His niece recalls that when he came to visit “there was a place for all of his paint equipment in his car and it would always go back exactly in the designated location along with luggage, picnic basket, etc.” He was also a proud and honest man. A friend asked Sammons to do some restoration work on a painting of birds. Sammons didn’t normally do restoration work but since a friend had asked he agreed. He finished the restoration and Queen liked the painting so much that she asked him if he would copy it for her. Sammons asked his friend for permission to copy the painting and she gave it. Sammons painted a copy; however, he never signed the work since he didn’t feel it was his creation. As a final point about his character, Sammons was a very humble man even as friends, fellow artists and art critics praised his work.

After a career that spanned more than fifty years, Carl Sammons died in Oakland on February 4, 1968. Services were held on February 6, 1968 at the Telegraph Avenue Chapel of the Grant Miller Mortuaries, Oakland. Sammons was survived by his wife (she lived to be 103 and passed away March 19, 1997 in Moraga, California); a sister, Mrs. Mary E. Dye, Petaluma; his brother, Roscoe C. Sammons, Long Beach; nieces and nephews. Both Carl and Queen were cremated and their remains interred at the Chapel of the Chimes, Oakland.

Painting was a lifelong passion for Sammons that began in his childhood. Like several other early California Impressionists, Sammons “was inspired to paint landscapes by his belief in God and his love of God’s creation.” Sammons began his formal art studies in Sioux City while working as a gold letter sign painter. During this time he studied under the leading local artist F. P. Frisch, a German painter. Around 1920, Sammons studied at the California School of Fine Arts (at the time affiliated with the University of California and now known as the San Francisco Art Institute). It seems likely that this is where Sammons studied oil painting. One newspaper article implies that Sammons may have studied with private instructors in New York and Germany. However, no other information has been found to validate this.

By his twenties, Sammons had developed a love of travel; something he would do for the rest of his life. In 1909 he joined two other “artistic sign writers”, Seal Van Sickle and Henry Schneider, touring South Dakota. Fittingly, Sammons was an early automobile enthusiast and, by the mid-1920s, used cars extensively in his work to make painting sojourns. Many of these painting trips involved Sammons and his wife camping out by the side of their car in scenic locations far away from any accommodations. These painting trips took them throughout the West and to many national parks including Bryce, Crater Lake, Glacier, Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, Yosemite and Zion. Sammons and his wife also made numerous painting trips within California to Humboldt County, the Monterey Peninsula, Palm Springs, the Russian River, Santa Barbara and the Sierra Nevada mountains. Sammons didn’t always drive to his painting locales. In 1924 he packed into the Piute Pass region of the high Sierras to paint that remote area.

During the late 1920s, Sammons was a well known and sought after artist. However, as with most artists, the Great Depression during the following decade was a very difficult time. Art was a luxury item and, as with his fellow artists, Sammons’ sales were hard hit by the economic troubles. In addition, as popular art styles changed to more abstract and modern techniques, Sammons chose to continue painting in the Impressionistic style. He was able to do this and make a living at it because he was a prolific painter, he sold his paintings at reasonable prices and he was a talented artist. It was during this time that John M. Gamble, the renowned early California Impressionist, praised Sammons as the best painter of flowers in the west.

Sammons painted a wide range of natural scenes. “His many works included landscapes, seascapes, high mountains, lakes, coastal ranges, the desert and its flora, rolling California hills, thundering breakers, scenes in all seasons, an occasional bouquet of flowers and even birds.” Within California, Sammons’ paintings include scenes from Antelope Valley, Big Sur, Cayucos, Contra Costa County (Mount Diablo and the Orinda hills), Death Valley, Humboldt County (Cape Mendocino, Davis Creek, the Eel River, the Etter Ranch, Ferndale, the Mattole River watershed, Petrolia and Shelter Cove), Laguna Beach, Mission San Miguel, the Monterey Peninsula (17 Mile Drive, the Carmel coast, the Lone Cypress, Monterey, Pacific Grove and Point Lobos), Mount Shasta, Palm Springs (Andreas Canyon, the Anza Borrego Desert, La Quinta Canyon, Mount San Gorgonio, the Palm Springs Desert and Mount San Jacinto), the Russian River (redwoods and the Russian River), the Sacramento River, the Salinas Valley (Camp Hunter Liggett and the San Miguel Mission), Santa Barbara (the Andre Clark Bird Refuge, Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Montecito, the Santa Barbara coast and the Santa Barbara Mission), San Diego (the Laguna Mountains), San Francisco (the Cliff House, Golden Gate Park and Sausalito), the Sierra Nevada mountains (Blue Lake, Convict Lake, Garnet Lake, Gull Lake, June Lake, King’s Canyon, Lake Diaz in Lone Pine, Lake Ellery, Lake George, Lake Mary, Lake Sabrina, Lake Tahoe, the Mammoth Lakes region, the Merced River, the Minarets, Mount Ritter, Relief Peak, Rush Creek, Silver Lake, the Sonora Pass, Tee Jay Lake, Twin Lakes, Virginia Lake and Yosemite) and Warner Hot Springs.

Sammons also painted throughout the West including Arizona (the Apache Trail, the Grand Canyon, the Oatman Mines, the Painted Desert, the Superstition Mountains, the Tucson desert, the Tucson Mission and the Virgin River Canyon), Colorado, Montana (Glacier National Park), Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon (Crater Lake and Diamond Lake), Texas, Utah (Bryce Canyon and Zion Canyon), Washington and Wyoming (the Grand Tetons, Jackson Hole, Jackson Lake, the Madison River, Mount Moran and Yellowstone). He painted in Nebraska (the Elkhorn River) and outside the continental United States in Alaska (Mount McKinley) and Canada (the Bow River and Lake Louise in Alberta).

Sammons had studios in a number of locations throughout California during his career. In addition to the studio in Monte Rio on the Russian River, Sammons maintained a studio in San Francisco during the mid-1920s. When he and Queen lived in Oakland, he also kept a studio there. Beginning in the 1930s and continuing into the mid-1950s, Sammons and his wife followed a yearly routine of traveling around California. They stayed in areas they liked for months at a time and went on painting excursions from these temporary homes. At these locales, Sammons would set up a studio. Other times, Sammons would make pencil sketches as he traveled to be used as a guide for painting in his studio.

Places they visited regularly where Sammons had a studio included Humboldt County (they loved Petrolia and spent the late summer and early fall there in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s), Palm Springs and Santa Barbara (they lived there in 1943). Even after buying a home in Oakland in 1956, they continued to travel around California, although not as much.

Sammons was a critical and commercial success in the 1920s and a commercial success again in the 1950s. He sold many of his works to individuals and public institutions through private exhibitions and personal contacts. Sammons even sold a few of his paintings to other artists. He sold a number of his paintings through art galleries in Berkeley; Carmel; Chicago; Cleveland; Palm Springs; San Francisco; Santa Barbara; Santa Rosa and the East. Like other artists, Sammons didn’t always sell his paintings and was known to give his paintings to his friends and occasionally in barter to pay his bills (i.e., the dentist, barber, etc.). Although one gallery and one auction house have written that Sammons had a patron, it turns out that in both cases, this was a barter arrangement with his dentist.

As many of his colleagues did, Sammons worked occasionally on commission. In 1926 he was commissioned to paint the Superstition Mountains in Arizona for the Elk’s Lodge in Oakland, the Apache Trail, and several paintings along the Lincoln Highway for “eastern automobile magnates who were officials of the Lincoln Highway Association.” During that same year, he was commissioned by the University of Arizona and the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce for works to be painted along the Apache Trail. In the 1920s, Sammons created a very large painting for California State Senator A. W. Way, a 60 x 240 in. work, showing the proposed Shoreline Highway from Sausalito north.

Sammons also painted a number of works to order for Donald Rheem; a friend and the developer of Rheem Valley (Moraga) in Contra Costa County. These included a 1940 oil painting titled “Mount Diablo Wild Flowers” measuring 12 x 16 in. and a circa 1950 oil painting titled “Rheem Valley Estate” measuring 36 x 54 in. Sammons was known to visit the location where the commissioned painting was to be displayed in order to choose the palette he used for the painting. He did this to ensure the finished painting would be complementary with its surroundings.

Notable California artists counted among Sammons’ friends included Edward Borein (1873-1945), John Gamble (1863-1957), Deidrich Gremke (1860-1939), Paul Grimm (1892-1974), Lorenzo Latimer (1857-1941), William Otte (1871-1957), DeWitt Parshall (1864-1956) and Thaddeus Welch (1844-1919). William Frates (1896-1969) who studied under him was also Sammons’ friend and best man at his wedding. Sammons would occasionally paint with his friends and colleagues, e.g., Sammons’ painting trip to the Grand Canyon in 1929 where he was to be joined by John Gamble and his painting trip in 1932 with Edward Borein.

Sammons knew Southern California artists as well. Around 1920, Sammons’ mother moved to Long Beach, California. Sammons would visit her and use the opportunity to make “trips to the art colony at Laguna Beach where he had many friends.” Sammons also knew Albert DeRome (1885-1959) and his “autograph” appears on the back of several of DeRome’s works. “It was DeRome’s habit to seek the advice of acquaintances when they visited his home. His visitors would then sign the backs of the paintings.”

When it came to art club membership, it seems that Sammons was a pragmatist, participating in organizations that gave him an active venue to exhibit and sell his paintings. In the 1920s, Sammons was a member of the Alameda County Art League, the Berkeley Fine Arts League and the Art League of Santa Barbara. In 1940 Sammons was a member of the American Artist’s Professional League (AAPL). He received an award from the League for “distinguished participation” in November 1940 for his involvement in the American Art Week exhibition held in Oakland. In 1941 Sammons was nominated for membership in the Society for Sanity in Art (later to be renamed the Society of Western Artists); however it is not known if he ever joined that organization. In 1942 he was a member of the Rocky Mountain Artists Association. Sammons was made an honorary member of the Redwood Palette Club, most likely in the early 1950s. Sammons may have been associated with the Desert Art Center, Palm Springs in the early 1950s as his presence in Palm Springs is mentioned in two Desert Art Center newspaper articles. However, the Desert Art Center’s remaining records from that period contain no reference to him.

As many artists did, Sammons willingly shared his knowledge of art with others. William E. Frates (1896-1969) studied under Sammons, as did Henry Vardon Going (1913-1954). Sammons was also known to give art advice when asked. For a short time, around 1960, he taught art students at his home in Oakland. However, Sammons soon found that many of these students asked for too much help and their paintings began to look exactly like his work. He didn’t feel that these students were expressing their own individual styles and he ceased formally teaching art.

The 1923 California Industries Exposition in San Francisco marks the beginning of Sammons’ public recognition as an early California Impressionist. In 1925 his work was exhibited at the Berkeley League of Fine Arts’ Third Annual Exhibition, Berkeley; in 1926 at the California Industries Exposition, San Diego; in 1926 at the Claremont Hotel Art Gallery, Berkeley; in 1928, 1929 and 1930 at the Art League of Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara (solo); in 1928, 1929, 1930 and 1931 at La Casa de Manana Gallery, Berkeley (solo); in 1931 at the Haggin Memorial Galleries, Stockton (now known as the Haggin Museum), (solo); in 1931 at the Tahoe Tavern, Tahoe City; in 1931 and 1933 at the Courvoisier Gallery, San Francisco; in 1939, 1940, 1941 and 1942 at the Desert Inn Gallery, Palm Springs; in 1940 at the Golden Gate International Exposition, San Francisco; in 1940 at the AAPLs American Art Week exhibition, Oakland; in 1942 and 1951 at the Abilene Museum of Fine Arts, Abilene, TX (now known as The Grace Museum); in 1946 and 1948 at the AAPLs American Art Week exhibition, Hayward; in 1947 with the Artists of Cathedral City, Cathedral City; circa 1947 at the William Keith Gallery, Saint Mary’s College, Moraga; in 1957 at the Alameda County Agricultural Fair, Pleasanton and in 1957 at the Crocker Art Gallery, Sacramento (now known as the Crocker Art Museum).

Sammons’ painting “Sacramento River Landscape” was exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. for the United States 1976 Bicentennial celebration. The Ronald E. Walker Collection contained Sammons’ works “Point Lobos”, “Lupines on the Anza Borrego Desert” and “Yuccas, Palm Springs Desert”. The Walker Collection was exhibited at the Nevada Museum of Art, Reno in 1993, the Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah in 1997, the Hearst Art Gallery, Saint Mary’s College, Moraga in 1997 and the Carnegie Art Museum, Oxnard in 1998. Sammons’ painting “Point Lobos” was displayed on the front cover of the book published in connection with the Nevada Museum of Art’s exhibit of the Walker Collection.

In 1994, a private collector loaned to the M. H. de Young Museum, San Francisco Sammons’ painting “Golden Hills of California” which was displayed in the museum’s galleries until 1999. Sammons’ work was displayed at the Irvine Valley College Art Gallery, Irvine in 2000 as part of the California Deserts exhibit. Two of Sammons’ paintings were included in the Palm Springs Art Museum’s “Treasures of the West: Art from Desert Collections” exhibit in 2007. In the summer of 2008, the Hearst Art Gallery, Saint Mary’s College, Moraga will exhibit (solo) Sammons’ paintings selected largely from the collection of his niece, Donna Walsh Sumner. This exhibit will be shown at the Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah in 2009.

Sammons’ paintings “Big Sur” and “King’s Canyon” are held by the M. H. de Young Museum, San Francisco. One of his paintings, a seascape titled “Ocean and Clouds”, is held by the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, Santa Barbara. The Grace Museum, Abilene, Texas holds Sammons’ painting “Desert Flowers.” His paintings are also held by the John Muir Medical Center, Walnut Creek; the Lakeshore Avenue Baptist Church, Oakland; the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga and The Santa Barbara Club, Santa Barbara.

The Inventory of American Paintings at the Smithsonian Institution; Washington, D.C contains listings of Sammons’ work. Slides of thirty-nine of his paintings are contained in the Nan and Roy Farrington Jones Archive of Early California & Western Art at the California State Museum Resource Center, West Sacramento.

Sammons didn’t participate in many public exhibits during his long career. However, when he did participate in public exhibitions it was alongside well renowned California artists. During his career some of the artists he exhibited alongside included Carl Oscar Borg (1879-1947), Jessie Arms Botke (1883-1971), Maurice Braun (1877-1941), William Clapp (1879-1954), Maynard Dixon (1875-1946), John Gamble (1863-1957), Arthur Gilbert (1894-1970), Selden Gile (1877-1947), Percy Gray (1869-1952), Armin Hansen (1886-1957), John Hilton (1904-1883), Maurice Logan (1886-1977), Jean Mannheim (1863-1945), Edgar Payne (1883-1947), Hanson Puthuff (1875-1972), Granville Redmond (1871-1935), William S. Rice (1873-1963), William Ritschel (1864-1949), Milliard Sheets (1907-1989), Jack Wilkinson Smith (1873-1949), James Swinnerton (1875-1974), William Wendt (1865-1946) and Theodore Wores (1859-1939).

At the 1923 California Industries Exposition, Sammons’ work first came to the attention of Harry Noyes Pratt. Pratt was well known in the art world and was, at various times, editor of the Overland Monthly, art critic for the Sunday San Francisco Chronicle, Director of the Haggin Memorial Galleries and Director of the Crocker Art Gallery. Pratt praised Sammons’ work on a number of occasions and the two became life long friends. Other critics appreciated Sammons’ work too. In the 1920s, Sammons was described as “one of California’s outstanding artists” and as a “famous western painter.” Sammons’ work was complimented by Florence Wieden Lehre, art critic for the Oakland Tribune, Assistant Director of the Oakland Art Gallery (now known as the Oakland Museum) and later Pacific Coast editor for the Art Digest. As previously mentioned, Sammons’ fellow artist John Gamble held his work in high esteem. During his life, Sammons’ paintings were sold to people with homes around the world; however, today he isn’t as well known as many other early California Impressionists.

Even as a relatively unrecognized artist today, his paintings have been auctioned at Bonhams & Butterfields, San Francisco; Christie’s, Los Angeles; John Moran Auctioneers, Pasadena; Sothebys.com; Phillips, London as well as other auction houses in the United States. In the last few years his paintings have been sold in art galleries in Arizona, California, Colorado, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina and Washington.

Sammons lack of recognition today may be due to several reasons. First, unlike many of his more renowned colleagues, it seems that Sammons chose to limit the amount of time and effort he spent vigorously promoting his art. Sammons was a very private man and it appears that he chose not to participate in many of the same activities that his peers did. Therefore, many of the records that art historians normally look at to support an artist’s place in history do not exist for him. After his passing, Queen wanted to respect his memory and to her that meant respecting his privacy. As a result, she was reluctant to talk to art historians about him so her knowledge of his contribution to early California Impressionism isn’t available to researchers.

Even though his wife helped market his paintings in various venues, for much of his career Sammons didn’t promote his paintings as actively as his contemporaries. However, there were a couple of exceptions. Early in his career, he convinced C. M. Bruner, owner of Bruner’s Art Gallery in Santa Rosa, California, to let him paint pastels in the window of the art gallery to draw in customers. Later in 1929, Sammons participated in an advertising campaign with the Durant Motor Company (an automobile manufacturer). Articles were written that highlighted Sammons’ use of his Durant Six Coupe during his western painting trips. These articles were printed in over fifty western newspapers.

In contrast, Sammons was inconsistent in naming his paintings in an ear catching or poetic manner. Some of his paintings drew praise for their titles but others were either untitled or had titles which were only descriptive of the scene they represented. On the other hand, Sammons painted for over fifty years and it would be difficult for any artist to create new and poetic titles for that long. In some cases, Sammons would sell his paintings on temporary matting and let the purchaser frame the painting which may have conveyed the impression that the work was not on par with a finished piece.

Even though Sammons called a number of well-known California artists his friends, he is known to have actively participated in only five art clubs throughout his long career; and three of those were during the 1920s. Also, unlike a number of his peers, Sammons does not appear to have participated in any of the social clubs (i.e., the Bohemian Club, etc.). Art and social clubs helped other artists promote their work and increased their historical recognition.

Sammons didn’t participate in many public or juried exhibits; preferring to sell his paintings through galleries, private exhibits and personal contacts. It appears that Sammons felt painting wasn’t a competitive endeavor but an act of creation in which each artist expressed his interpretation, each equally valid, with the ultimate verdict lying in the hands of the purchaser of the painting. However, by not participating in juried exhibits, he excluded himself from the possibility of winning awards, another way that artists gain historical recognition.

Sammons level of participation in clubs and juried exhibits were at least partly due to the result of conflicts with his painting trips. In the 1920s Sammons traveled to some distant painting locations by himself however by the 1930s he and Queen always traveled together and loved their annual trips around California. Both he and Queen rarely spent more than three or four months a year in any one location making it difficult to be an active member in any organization. They developed a routine, traveling to Santa Barbara in the late fall, then on to Palm Springs for the winter, then back north to Carmel and the Sierras ending up in Humboldt County for the late summer and early fall. Sammons would exhibit his work in local venues along his route of travel and rarely elsewhere. Therefore, their yearly travel took precedence over broader promotional considerations for most of his career.

In summary, it seems that Sammons promoted his work only enough to make a reasonable living. This in turn though allowed him to focus on what he loved; spending time with Queen, painting and traveling throughout California (and the West).

Second, some of the technical aspects of Sammons’ paintings may be viewed as less sophisticated than his peers. While Sammons’ technique improved over his career his brushstrokes remained deliberate, measured and generally ordered resulting in a well defined composition. This may be interpreted by some as being too precise for an Impressionistic work and hence lacking in sophistication.

With regard to his palette, Sammons typically used a few pure or strong colors set amid a number of more subdued tones (possibly harking back to his earlier Tonalist days). Many of his more renowned Impressionistic peers used palettes that were more complex than this. They used either subtler shades of color or color contrast to form vivid color values. Therefore, these artists may be perceived to have used more refined color techniques.

Nevertheless, many examples exist, both in oil and pastel, where Sammons’ paintings exhibit sophisticated brushstrokes and color values. It is worth noting that Granville Redmond’s brushstrokes are deliberate and measured in a manner similar to Sammons’ brushstrokes. Also, John Gamble used strong color in his paintings. Both artists are highly regarded early California Impressionists. Speculatively, given the relationship between them, it’s likely that Sammons was influenced to use strong color in his paintings by John Gamble.

Finally, Sammons lack of recognition may be due to the fragility of many of his works. Most of Sammons’ pastels were painted prior to 1940 and many of those have probably not survived to the present day. Sammons painted many pastels with rich, vibrant color; however they are rarely seen in art venues today. Since pastel works are more delicate than oils and must be properly maintained in order to stand up to the tests of time, it’s reasonable to assume that many of his pastels have not survived into the present and therefore are not available for study.

However, there is a professional art researcher who recently viewed a collection of Sammons’ pastels and that is Alfred C. Harrison, Jr. of The North Point Gallery in San Francisco. He wrote “I don’t think America produced a better pastel landscape painter than Carl Sammons, and I’m not forgetting William Merritt Chase or the California pastel painters Jules Tavernier and Charles Dormom Robinson when I express that opinion.”

Although Sammons’ early works are painted in the Tonalist style, the majority of his work is a combination of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and the American Realist tradition that fits squarely into the California Eucalyptus School of painting. Just as it is important to describe the style Sammons used, it is equally important to describe what his method does not include. Sammons’ was not a Modernist. His paintings are not Symbolic, Abstract or Expressionist; nevertheless, they do embody a spirituality of the land.

Sammons’ early pastels contain many Tonalist elements. These early paintings portray nature as idyllic and serene. Sammons used narrow, yet harmonious ranges of color along with diffuse lighting to evoke these peaceful and quiet moods. Once Sammons began painting in the Impressionistic style, his palette (for both his pastels and oils) became more complex and colorful. Sammons seems to have made the transition from Tonalism to Impressionism around 1920, slightly after other California artists. It was at this time that art critics began to take notice of Sammons’ work and praise it.

During Sammons’ career, California changed considerably yet his focus remained on landscapes. California’s population grew from about two and a half million in 1910 to slightly over nineteen million by the time of his death in 1968. Industry and development became increasingly important to the state’s economy and many places which, in 1913, were remote or scenic became easily accessible or developed by 1968. As development increased, the desire to protect scenic areas, preserve open space and curb growth grew within the state. During the same time frame, the United States went through considerable changes including an isolationist period, a severe depression, two world wars, its emergence as one of the world’s two superpowers and social unrest. However, there is no indication that any of these factors influenced his work; only that he loved the scenery he painted.

Some believe that Sammons was “inspired by the compelling aesthetic beauty of canvases by a somewhat older generation of early California artists such as Granville Redmond (1871-1957), John Gamble (1863-1957) and Percy Gray (1869-1952). Carl Sammons was also attuned with artists of his generation such as Edgar Payne (1883-1947), Albert DeRome (1885-1959) and Paul Grimm (1892-1974). It is worth noting that Sammons was actively painting California imagery in the same locales and during the years overlapping all six of these artists.” While Sammons was aware of the work of his peers, it seems that he was inspired more by the natural beauty around him.

“His early canvases are generally more tonal renditions in the pastel palette of impressionism and characterized by medium width broken brushwork applied in a layered, craftsman-like manner. Eventually, by the late 1930s, he began using a narrower, more representational style of broken brushwork, while employing a higher key of color values to represent nature’s palette.” Sammons’ paintings “are recognizable for their strong color and well defined composition.” Besides oil and pastel, Sammons worked in two other mediums: watercolor twice during his infrequent illnesses and in gouache.

Sammons’ oils are typically recognized as including a vivid color component; however, his pastels are not. In truth though, his pastels exhibit a broad range of color extending from restrained to vibrant. In the early days of his career Sammons bought his pastel supplies from his former mentor F. P. Frisch. Later, possibly after F. P. Frisch had passed away, Sammons made “his own crayons in colors that cannot be bought. The result is that no blending is necessary and the finished painting gives a fresh color effect similar to water color technique.” John Gamble described Sammons’ pastels in one exhibit as “little gems possessing a richness of color one seldom sees in this difficult medium.”

As noted earlier, Sammons painted a few large works on commission. However, unlike many of his well-known peers, Sammons doesn’t seem to have painted many larger pieces instead preferring smaller canvases. There may have been two reasons for this. First, Sammons was a true Plein Air artist; one who used his car to travel to remote locations in order to paint them. The cars he used could not accommodate very large canvases. Secondly, Sammons painted on smaller canvases to paint works that were more affordable and saved a little money on materials. He was known at times to purchase a 24 x 30 in. canvas board, paint the backside green, and then divide the board into four, 12 x 15 in. sections for his paintings.

Interestingly, Sammons also occasionally painted miniatures. These paintings were 2 x 3 in. and required great skill to paint an Impressionistic work in such a small area.

Sammons would usually sign his paintings at the bottom (on either the right or left side) as Carl Sammons, C. Sammons, or Sammons. On several occasions, he signed only the matting on which he had mounted the painting.

Carl Sammons excelled at painting both oils and pastels. He combined Impressionistic and Post-Impressionistic techniques to create very sophisticated canvases. As such, his finest works are comparable to those produced by his more renowned early California Impressionist colleagues. However, Sammons’ desire to paint the landscape he loved took precedence over promoting his work and has caused his paintings to be overlooked by many modern scholars and collectors. As time passes, and more people become familiar with his legacy, Sammons’ paintings will come to be known as an important contribution to the early California Impressionist tradition.

Share